Do More with Less (Noise)

“I think we all know times are tough, and we’ve had to say goodbye to some of our colleagues this week due to the CoVid-19 downturn in business.” their leader pronounced. The all-hands meeting had just started. “Our priorities haven’t changed and you’ll have to take on most of the initiatives that your former colleagues were working on. We’ll just have to figure out how to do more with less!”, she exclaimed. Everyone looked around the virtual table, eyes were averted, arms crossed, a few sighs. Nobody spoke, but everyone was thinking the same thing; we can’t even do what we need to today let alone do more. Most people were already meeting through lunch, answering emails after their kids went to bed, and often worked on the weekends. Nobody could imagine taking on more, but they always did.

As an agile coach, everywhere I look, I am surrounded by people who desperately WANT to do a good job. They work in organizations that they believe in. They take their careers seriously. They look for opportunities to improve. They take on whatever is asked of them. Yet they often find themselves drowning; sometimes paralyzed, with NO TIME to do their work to the best of their abilities.

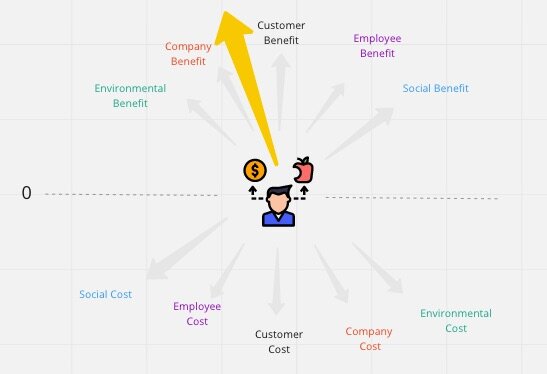

The problem, of course, is that the directive “Do more with less” is focused on DOING. It encourages a culture that values ‘being busy’ over delivering customer value. In this type of culture, busy-ness is rewarded and reinforced through a focus on ‘resource utility’ - the drive to ensure that a person’s time is entirely allocated. It’s a mindset that encourages people to join more initiatives and to always say ‘yes’ regardless of workload because being in demand, being busy, is equated with value to the organization. This mindset, and the accompanying structures and processes, are designed to optimize for people’s time spent on activity because, after all, people are expensive. The flaw in these traditional systems is that they are designed to focus on costs instead of focusing on how to best deliver value. In doing so, many organizations have actually ended up increasing the cost of delivering value to their customers.

The way to ACCOMPLISH more with less, is to DO less to accomplish more. This is described succinctly in Principle 10 behind the ‘Agile Manifesto’;

“Simplicity–the art of maximizing the amount of work NOT done–is essential.”

In agile terms, this means focusing on the business outcome at hand and not allowing yourself to be distracted by things you may or may not need in the future. I think of this as cutting out the noise. You needn’t be an agilist for this to be true. For most people the best way to deliver more is to change two things: 1) focus on fewer goals at any given time and 2) simplify the communication surrounding those goals. Fewer goals means less context switching. Reducing context switching alone will provide space for clearer communication, and if you also apply intentional communication conventions you will further reduce the noise and increase the flow of value. You’ll actually be doing less but delivering more.

Noise is a measure of an organization’s dysfunction and finding ways to reduce that noise is a behavioural wedge to shift the organizational culture to one that truly focuses on delivering more value by doing less!

Evidence of Noise in Your Organization

Here are some common examples of things I hear in the initial stages of working with a new team or organization:

“I’m looking forward to a long weekend to get work done with no meetings!”

“It’s only Monday afternoon, I haven’t gotten to that email yet.”

“I am usually in about 12 back-to-back meetings every day“

“Where did all these meetings pop up today from?”

“Not another meeting over lunchtime”

“I usually go home and take care of emails in the evening“

These same people often have calendars and inbox(es) that look like this and worse:

Does this seem familiar? All these meetings and emails are evidence of a plethora of communication paths and context switching. The result is that people are spending most of their time communicating and context switching rather than accomplishing things. Yes, communication is definitely a major part of all work. Yes, communication and collaboration are required to accomplish goals. But for so many people, there is no time left to actually think and act when so much of their time is spread thinly across too many scattered, frequent, noisy communication paths.

In this three part series, I’ll be discussing how the noise in your organization is preventing you from doing more with less and how to change that. I’ll cover the first of the two main culprits, division of time and attention here, and follow-on in my next post with the impact of not having explicit communication conventions.

Division of Time and Attention

People in most organizations experience an endless division of their time and attention as they become involved in too many projects/initiatives/teams simultaneously. Each of those endeavours incurs an increase in things to be prioritized, people and information to stay current with, and often unrelated tasks to be completed. This forces numerous context switches daily and sometimes hourly. Most organizational systems reinforce this behaviour - maximizing the utilization of people’s time. Time is a valuable commodity and so, the logic goes, the less time I have available the more valuable I must be. If my calendar is full, I must be indispensable! As a result we find ourselves “working off the side of our desk”. We’re late for meetings; we’re not fully prepared for the meetings we do attend; we don’t have time for the appropriate follow up to those meetings. While we’re in a meeting we’re responding to texts and slacks as they steal our attention. We’re relieved when a meeting is cancelled because it frees some time to follow up on something else. It is a never ending vicious cycle of wanting to be involved, but only able to partially pay attention. In all this, there is too much noise and not enough signal. Not enough time to do what we know is required of quality work.

There’s lots of talk about whether we can truly multi-task. I believe this is asking the wrong question. The fact is, people feel the need to multi-task all the time. When we are multi-tasking (no doubt in an effort to increase productivity), what are the costs? It may seem trivial to switch between two simple tasks, but our work is often composed of complicated tasks solving complex problems.

There are a myriad of psychological studies dating back to the 1980’s exploring the costs of context switching while multi-tasking. These studies invariably conclude that the time and energy it takes to context switch result in poorer outcomes, and those outcomes take longer to achieve. According to D.E. Meyer and his research from 2001 ("Executive Control of Cognitive Processes in Task Switching") the cost may be as much as 40%. What could we accomplish with 40% more time to focus?

My colleague Roger Brown wrote an article in 2010 discussing the implications of multi-tasking for people working on multiple projects. He also illustrates the impact of multi-tasking on ‘time-to-value’ for organizations working on multiple initiatives simultaneously with the same people. It’s been shown over and over again that we’ll get things accomplished faster if we focus on only a very few things at a time. Complete them and move on to your next priority. Repeat. Teams need to be designed to enable that.

In their 2011 paper entitled “Multi-Team Membership: A Theoretical Model of its Effects on Productivity and Learning for Individuals and Teams”, O’Leary, Mortenson, and Wooley discuss the prevalence of people working as members of multiple teams (MTM) across a myriad of industries. They found a decrease in productivity across the board due to the high cost of context switching. Most compellingly they found that it is usually individuals (and their families) paying the true cost of the overhead due to context switching.

“... we found significant work-life issues arising from MTM. Managers and employees report that the time required to accommodate the additional overhead caused by work on multiple teams is most frequently taken from personal or family time, leading to significant work-life tension. The ways in which these tensions are viewed and handled is dependent on the underlying organizational culture.”

Undeniably, context switching due to multi-team membership leads to poorer outcomes for both the organization and the individual. Further, it takes more time for those poorer outcomes to arrive.

What Organizational Principles Decrease the Noise?

Queuing Theory and Batch Size

It is well known from the Queuing Theory, and concepts illustrated by Don Reinertsen in his 2009 book “The Principles of Product Development Flow“ that reducing ‘batch size’ increases the flow of value through a system. Small batches lead to greater throughput because doing so changes the focus from optimizing resource allocation for local task efficiency to optimizing resource allocation for value through the whole system. As individuals, when we are involved in many initiatives, effectively we have a very large batch size. The individual tasks we perform may be done quickly but the overall value we deliver moves slowly due to constant context switching and delays by everyone involved. Reducing our batch size (fewer initiatives demanding our time and attention) can increase the flow of value through the organization. We don’t need to reach the ideal of being a member of a single team that is singularly focused on one product, but we do need to recognize that fewer initiatives simultaneously for any individual will lead to greater flow of value.

What would happen to your productivity if you could reduce your batch size? What would happen to your team’s productivity if their batch size was reduced? Would you accomplish more for less?

Conway’s Law

In alignment with Conway’s law (“Any organization that designs a system will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization's communication structure”) some organizations are adopting small multi-disciplined team structures focused on time-to-value for customers. Fausto de la Torre does an excellent job of illustrating Conway’s Law in this posting where he gives a very clear example of the relationship between team structure and product outcome.

Does Conway’s Law apply to your organization? Ask yourself whether the products you build reflect the characteristics of an organization with noisy communication paths. Does it take a long time to get to value? Do the outcomes exhibit signs of disjointed thinking or ownership? Would your customers say your products are cohesive and fit for their purpose? Sometimes these answers are hard to face.

Effective Teams

In his book Collaborative Intelligence, Richard Hackman (Harvard professor of social and organizational psychology) sets out six basic conditions that leaders of organizations must fulfill in order to create and maintain effective teams. This is based on his 40 years of research into team performance and effectiveness.

Create Real Teams. People have to know who is on the team, who is not, and that the team membership is stable.

Specify a Compelling Team Purpose. Members need to know, and agree on, what they’re supposed to be accomplishing together.

Put the Right People on the Team. Teams must have the right number of people with the right mix of technical and social skills to solve the problems.

Establish Clear Norms of Conduct. Clear ground rules for how members expect each other to behave helps create a collaborative and effective team culture

Provide Organizational Supports for Teamwork. The organizational context (e.g. compensation/incentive system, the HR system, and the information system) must facilitate, and certainly not detract from, teamwork.

Provide Well-timed Team Coaching. Teams need coaching as a group in team processes—especially at the beginning, midpoint, and end of a team project.

While I believe all six of these conditions are critical to team effectiveness, of particular interest to this discussion are 1,2, and 3. Creating ‘real teams’ means limiting the focus of the members of the team and providing stability in membership. It does not mean that everyone is on 4 teams! Specifying a compelling purpose means that the team has common goals and priorities which would otherwise be scattered and misaligned. Putting the right people on the team creates autonomy for the team to accomplish their stated purpose. These conditions together significantly reduce Noise by limiting context switching to the common priorities of the team.

So What To Do?

What Can Individuals Do?

For Individuals, regardless of your team/org structure, it is important to look after yourself. This may require courage in an organization that isn’t supporting you appropriately. Even if you feel powerless to change anything for the organization the following approaches will shed intense light on your own real capacity (not aspirational capacity) and on your healthy limits. Depending on your organization’s culture these changes in your approach will allow you to engage in better conversations with your colleagues about priorities, value, and capacity. Model the way. You may be surprised by the results.

Make your current priorities regularly visible to the people that put demands on your time; above, below, and beside you. Discuss with your colleagues the items that are outside your capacity at the moment.

Based on your knowledge of the work involved in your priorities and the meetings required, block out time to prepare and followup. Do not allow yourself to get double-booked. Minimize your context switching by working your priorities based on value and not letting lower priority interruptions distract you.

Instead of saying ‘No’, change the conversation to ‘Where does this fit with the existing priorities’?

Modelling these behaviours might start the process of shifting the organizational culture, but it will definitely give you clarity.

What Can Teams Do?

For teams, regardless of their structure (project, functional, component, or product-based) simply getting visibility into priorities, capacity, and dependencies can make a huge improvement to the flow of team outcomes. The following approaches will help you find ways to expose the costs of context switching experienced by team members.

Make the team’s current priorities regularly visible to the rest of the organization and especially to the people and/or other teams for which there are dependencies

Based on the team’s knowledge of the work involved in it’s priorities, establish a rolling capacity for the team and constantly evaluate whether the team is working the right priorities

Make the team’s dependencies visible so you can also make the costs of delay (due to mismatched priorities/availability) visible

Modelling these team behaviours nudges the organization toward a more agile culture

What Can Organizations Do?

For organizations, an iterative/incremental transition to stable, customer focused, multi-disciplined product/service teams usually significantly decreases time-to-value, provides more flow through the system, AND decreases the noise experienced by most people. Here are some of the steps you can take.

Iteratively refine team structure to reduce external dependencies

Create organizational support for teams to focus

Identify organizational capacity based on stable teams and bringing work to the teams

Refine organizational structures to move prioritization and funding decisions nearer the true arbiters of value

These are just a few of the approaches I’ve been using to help people, teams, and organizations accomplish more with less noise. It takes discipline and consistency for real change to take hold. I have seen it happen.

In my next post I’ll look at the second culprit creating noise in your organization - a lack of communication conventions.