Behavioural Economics: Lessons in Leadership

Richard Thaler, a recent Nobel prize winner in Economics from the University of Chicago has changed the way many economists think about their economic models by including elements of psychology. This is known as Behavioural Economics. Rather than assuming that the entities involved in the models make rational decisions for their well being, Thaler has popularized the idea that those entities should reflect the reality that people make decisions that undermine their overall long-term being.

Last month I had the good fortune to listen to the Oct 25 episode of the Freakonomics podcast entitled “How to Launch a Behaviour-Change Revolution”. During this 45 min podcast, the hosts explore the genesis of Behavioural Economics and a research project called “Behaviour Change for Good”; a play on words for positive, long lasting change. This research by Angela Duckworth and Katherine Milkman had the goal of helping people make truly lasting behaviour change by helping them make better decisions for their overall long-term being.

THE EQUILIBRIUM OF CHANGE

As a kickoff to their research project, Duckworth and Milkman hosted a two day summit attended by luminaries from the field of psychology, including another Nobel prize winner Daniel Kahneman. You may know Kahneman from his work on cognitive biases as discussed in his book “Thinking Fast and Slow”. During the 2nd day of the summit (30 mins into the podcast) Kahneman comments on ‘the best idea I ever heard in psychology’. The idea he refers to is from Kurt Lewin, a German-American psychologist from the early 20th century. Lewin’s idea was that in thinking about behaviour, we should consider that there are always two opposing external forces; driving forces and restraining forces. His novel insight was that behaviour is really the equilibrium between those forces.

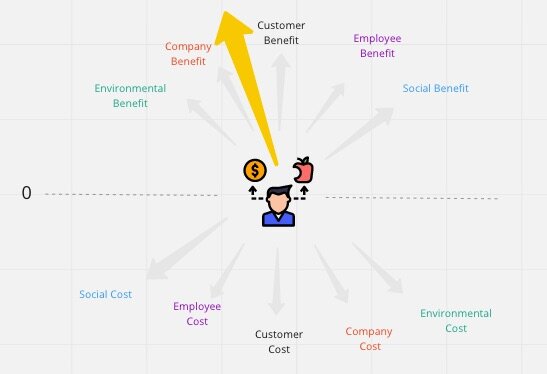

Therefore, when trying to induce change in behaviour, one can choose to either reduce the restraining forces or increase the driving forces. Our natural predisposition when changing anything is to increase driving forces. When we want to move an object, we move it. When we want to change a person, we try to cajole and incent in order to change that person. Kahneman argues that we need to change our perspective and instead of asking ‘How can we get this person to do X?’, instead ask ‘What is preventing this person from already doing X?’ Lewin asserted that reducing the restraining forces is usually much more effective than increasing the driving forces. Those restraining forces are likely reflective of the system within which the person is working. Changing behaviour involves changing the constraints within the system.

Consider the significant implications this has for leadership. Rather than trying to directly change a person’s behaviour, leaders need to be asking what they can do to make it easier for the person to change their behaviour; to reduce the restraining forces. Kahneman states that the way to make things easier is almost always controlling the person’s environment. Whether it’s changing counterproductive incentives, social pressure, or any other organizational impediment, the premise is that if A is a restraining force on B then let’s work on reducing A not driving B.

OVERPROMISING

Later in the podcast Kahneman is challenged on his assertion that “you have to overpromise to get ANYTHING done”. After all, he has done the seminal work on cognitive biases that lead us, as a psychological mistake, to be overly optimistic. Kahneman maintains that making practical incremental improvements in results may be useful but to really make a difference, to create ‘big successes’, likely requires being unreasonably optimistic at the outset.

This concept also has implications for leadership. My experience applying Scrum values and principles to the execution of large oil and gas construction projects mirrors these assertions. The EPCM team’s success on a $2.4 billion program of three natural gas processing plants was in part due to the team’s commitment to goals that seemed entirely unreasonable at the time. According to McKinsey, the global normal performance for mega-projects (>$1B) in this domain is a cost overrun of 30-40% and a schedule overrun of 40-50%. The EPCM leadership team and the execution team collaboratively set their sights on being 10% under budget and months ahead of schedule. Our approach to achieving these results was to acknowledge that we didn’t know HOW we were going to solve the problems in front of us but that we were going to commit to regularly understanding our current priorities, and then tackling each seemingly unsolvable problem one at a time as a multi-discipline team. We didn’t solve all of them, but we solved most of them. The EPCM leadership also focused on reducing restraining forces by removing impediments preventing team members from working collaboratively. Namely, co-locating the team, implementing cross-discipline team composition, and promoting the idea that the identification of upcoming problems was a vital and important activity. The results were that the first plant was in service 38 days early, the second was in service 86 days early, and the third was in service 167 days early; the plants were delivered 10% under budget. This had immense implications for the economics of the projects as revenue was generated early.

“If you solve one problem, and the next one … if you solve enough problems you get to come home.” - Mark Watney, The Martian

As always, we prosper from conversations with our colleagues outside of our immediate domain.